Golden Valley Starts ‘Just Deeds Project’ to Help Citizens Remove Racial Covenants

Did you know the property deed to your home may contain racist language? Racial restrictive covenants were prevalent during the first half of the 20th century. The policy prevented people of color and other groups from living in specific neighborhoods. Although these contracts have been illegal for decades, they are still impacting communities like Robbinsdale and Golden Valley.

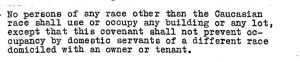

Miguel and Maria Cisneros of Golden Valley discovered racist language on their property deed.

“This house that we own had a racially restrictive covenant,” said Maria Cisneros, who is also the Golden Valley city attorney. “We found it in the documents when we were purchasing the house.”

The racially restrictive covenant would have prevented Cisneros’ husband Miguel, who is from Venezuela, from living in the home.

Deed from property of Miguel and Maria Cisneros. This covenant would have prevented Miguel Cisneros, a native of Venezuela, from living in the home.

“I was very upset,” said Miguel. “I felt very aggravated. It was like the first time I felt racism against me.”

Eventually, the Cisneros family had the racist language removed from their deed. But Miguel didn’t understand why the language was still on the legal paperwork.

“By the fact that it was still there, it makes me feel like why do we continue having this? Why hasn’t someone not taking this down?” asked Miguel.

That’s what Maria wanted to find out too. She decided to look into city records and find other restrictive covenants.

“One of the things I like to look at when I’m researching this is the social conditions that were happening when those developments were taking place that made people feel like that was something they wanted to do,” said Maria.

The Tyrol neighborhood in Golden Valley had racial restrictive covenants.

New Tool to Discover Restrictive Covenants

You can see precisely where covenants were enforced on an interactive map by the University of Minnesota’s “Mapping Prejudice Project.” Blue dots on the map fill the border of Minneapolis and Golden Valley.

“The patterns are so strong, so striking,” said Kirsten Delegard, co-founder of the Mapping Prejudice Project. “The developers were super careful when they developed right on the Minneapolis border to make sure it was racially restricted.”

During the development of Golden Valley, there was an effort to ensure it was an all-white community. Deeds for several homes in Golden Valley’s Spring Green neighborhood, near Highway 100 and Interstate 394, have racially restrictive covenants. Community developers and even city officials were complicit in using restrictive covenants.

“I found planning commission and city council minutes from the city of Golden Valley from 1938 that had a requirement that the developer put the covenant in the development agreement,” said Maria Cisneros.

The U.S. Supreme Court made restrictive covenants illegal in 1948, but people continued to use the contracts, privately.

“Making them illegal was not enough to change the demographic patterns once they were established,” explained Delegard.

The racist contracts created homogeneous communities. They also caused concentrated wealth within the white population, Delegard said.

“They signaled to investors, to developers, to policymakers that these areas that had covenants were safe places for investments,” she said.

The neighborhoods that had covenants also got more investments, everything from parks to street improvements.

“A house that had a covenant on it, compared with a house that didn’t have a covenant, even if they were identical in the same neighborhood, the house that had the covenant today is worth 15 percent more,” remarked Delegard.

Golden Valley Launches ‘Just Deeds Project’

In 2019, the Minnesota Legislature passed a law to allow homeowners to remove the restrictive covenants on their properties. The Golden Valley Human Rights Commission recently started a program called the Just Deeds Project, which provides free legal and title services to help people remove the racially restrictive language.

“We are working to not only raise awareness but, to figure out what we can do to right this historical wrong,” said Chris Mitchell, vice chair of the Golden Valley Human Rights Commission.

While some might say removing derogatory language off property deeds merely is symbolic, others like Miguel, say it goes much deeper than that.

“The feeling of it is still there,” said Miguel Cisneros. “It’s like having a sliver on your finger, a piece of wood that is bothering you.”

Golden Valley officials say they want to educate residents and foster a more inclusive environment. They also hope this opens up conversations.